Neighbors help neighbors overcome dialect challenges

As Mexican, Guatemalan, and other Central American immigrants settled into the rural town of Collinsville, locals adjusted to the new culture, a blend of the traditional southern United States and of Latin America. However, one big misconception persists among locals that all Latin American immigrants speak Spanish.

According to “Alabama Al Día,” a publication produced by the Alabama Center for Traditional Culture in partnership with the Alabama Latin American Association, “Many of the Guatemalans in Alabama are Mayans from the highland areas of their country. Here they live primarily in Mobile and Baldwin County in south Alabama, and Collinsville, Blount County and Birmingham in north Alabama.”

Though Spanish is the primary language in Guatemala, they are 22 Mayan languages officially recognized as well as two other indigenous languages. Due to immigration, Collinsville is home to Mayan languages, too.

“In Alabama [Quiché, Kanjobal, and Mam] are spoken as well as small populations who speak Chuj and Poptí. According to Miriam Arqueta, a Mayan interpreter who works for the Walker County health department, if adult Mayans have a second language in Alabama, it is usually Spanish instead of English,” according to an article in Alabama Al Dia.

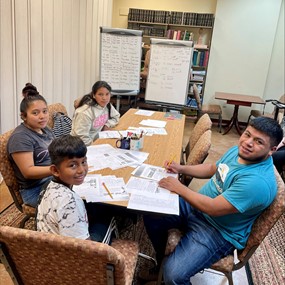

Robin Rowan, English as a second language teacher at Collinsville Public Library, experienced firsthand the language diversity in Collinsville when a sweet 17-year-old girl started coming to her Tuesday and Thursday English classes.

At first, she thought her new student was simply shy but soon began to suspect that Spanish was not her first language. During class one day, when asked to write a sentence in English, the girl muttered, “No puedo,” and from there, Rowan quickly discovered that her student spoke extremely limited Spanish and could not read or write in any language.

Rowan realized that she was tasked with teaching an illiterate young adult to speak English with no common language spoken between the two. “Students like this are a challenge,” she said. “The main thing is to be patient, positive, and kind in order to build their confidence and encourage them not to give up.”

That is the same story for many dialect speakers in Collinsville. With no literacy or Spanish skills, these immigrants are left with no official resources for navigating the extreme language barriers before them.

Luckily, another young girl who began attending the class, Sherlyn Juan, was able to speak Akateko, the dialect native to Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Sherlyn’s mother is Mayan, and her father is not, so she was raised bilingual.

Sherlyn was happy to help translate, and the two spoke quickly, revealing details of the student’s life that Rowan would have otherwise not been unable to uncover. The support system for indigenous immigrants in Collinsville comes from community members like Sherlyn, good Samaritans willing to help where needed.

“It’s important for me to know Akateko because there are people [in Guatemala and the U.S.] who don’t speak Spanish, and I can help them,” Sherlyn said. According to her, there are no resources where she’s from for indigenous speakers to learn Spanish either.

Remigio Solis, a long-time community member in Collinsville, came to the United States speaking Chalchiteko, another dialect native to Huehuetenango. Now trilingual, he began his language journey in 2008 reading books in Spanish, four years after he arrived in Collinsville.

During his first few years in Alabama, Solis rarely went out and kept to himself partly due to a language barrier, he said. He would navigate everyday interactions like shopping at stores using gestures and pointing to communicate.

After learning Spanish, Solis tackled English by attending English classes at Collinsville Public Library. “To me, who helped me more, it’s the teachers. They talked to me and were nice,” Solis said.

Now, Solis works with his church to help community members just like him. “In my opinion, it is not a problem if people come here, and they don’t know English, if they don’t know Spanish, if they’re shy. It’s okay. The problem is if they stay there doing the same thing because nothing is going to change unless you do something,” he said.

“We help each other. If somebody does not know English or Spanish, I help them,” Solis said, sitting in the very library where he learned English himself.

Tags: Collinsville